Ever read a poem and felt a profound connection, or perhaps a ripple of confusion, wondering how the poet managed to evoke such specific feelings or images? The magic isn't accidental; it's meticulously crafted through the interplay of literary devices and poetic structure of the poem. These are the hidden gears and springs of verse, the secret language that transforms mere words into an experience. Understanding them isn't just about acing a literature test; it’s about unlocking a richer, deeper appreciation for the art of poetry itself, empowering you to move from simply reading a poem to truly experiencing it.

At a Glance: Decoding Poetic Magic

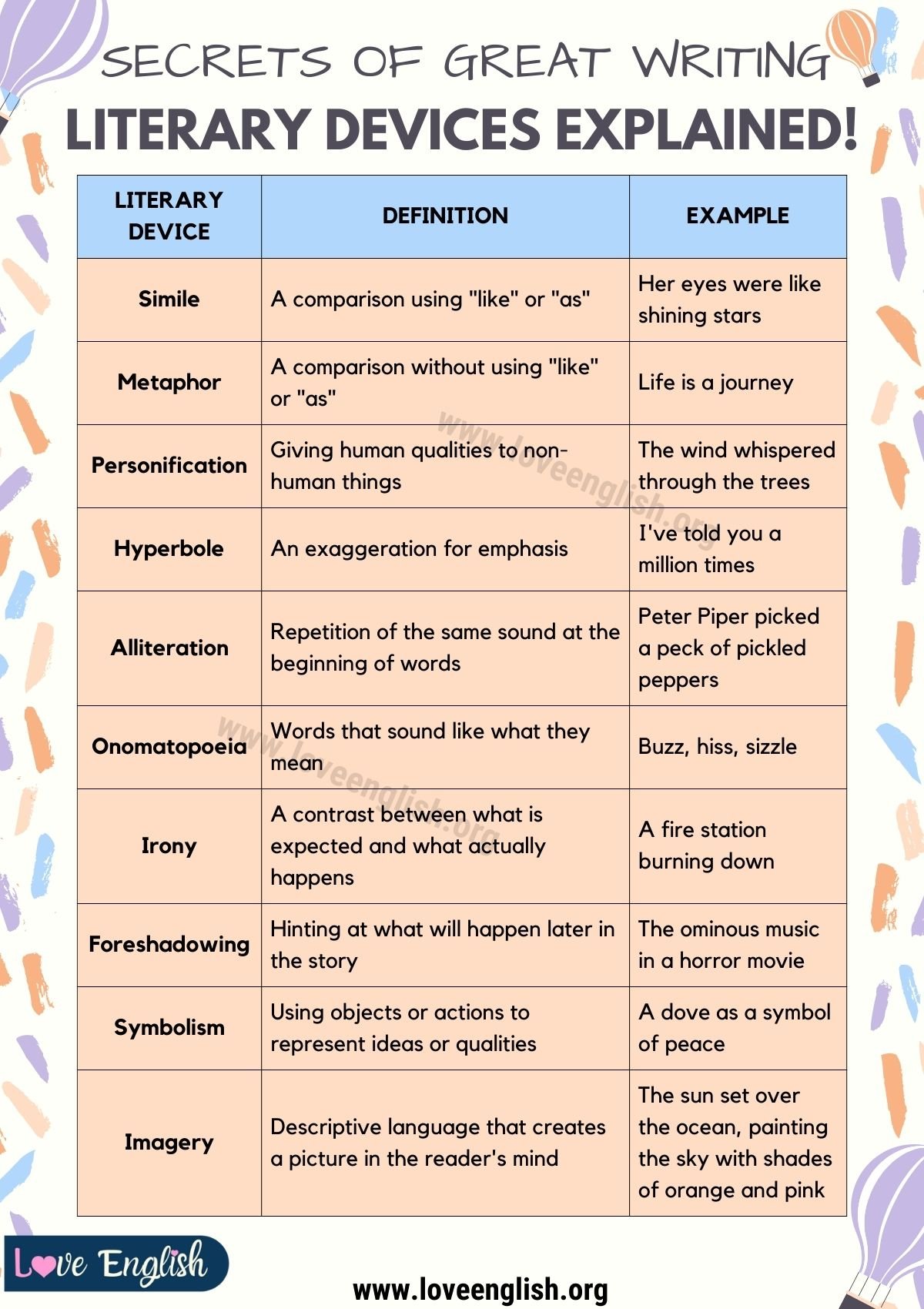

- Literary Devices are the writer's toolkit—techniques like metaphors, alliteration, and imagery that add depth, meaning, and sensory appeal.

- Poetic Structure refers to the poem's blueprint, including its meter, rhyme scheme, stanza forms, and line breaks, which dictate its rhythm and visual organization.

- Why bother? These elements work together to create a poem's mood, convey its themes, and guide your emotional response.

- Analysis is a process: Start with overall impressions, then dive into specific devices and structural choices, always asking why the poet made those choices and how they impact the meaning.

- It's not just for experts: With a few key terms and a systematic approach, anyone can uncover the layers of meaning within a poem.

Understanding the Poet's Blueprint: Why Structure and Devices Matter

Think of a poem as a meticulously built house. The poetic structure is its architectural design – the number of rooms (stanzas), the type of foundation (meter), how the walls connect (rhyme scheme), and where the windows are placed (line breaks). It provides the framework, dictating the flow, rhythm, and even the visual appearance of the verse.

Meanwhile, literary devices are the interior design elements and functional features: the evocative colors (imagery), the intriguing artwork (metaphors and similes), the subtle lighting (allusion), or the recurring decorative motifs (refrain). These techniques enrich the house, giving it character, atmosphere, and a story to tell.

Without understanding both, you're merely walking through a building; with them, you begin to grasp the architect's vision and the designer's intent, truly appreciating the craft. They are the primary tools poets use to distill complex emotions, ideas, and narratives into concise, impactful forms. They sculpt sound, meaning, and feeling, transforming ordinary language into something extraordinary.

Decoding the Words: Essential Literary Devices for Poems

Literary devices are the special effects of poetry. They're not just ornamental; they actively shape meaning, evoke emotion, and engage your senses. Here are some of the most crucial ones to recognize:

Figures of Speech: Crafting Imagery and Meaning

These devices play with language, often using words in non-literal ways to create vivid pictures or deeper implications.

- Metaphor: A direct comparison between two unlike things, stating that one is the other, without using "like" or "as."

- Example: "The moon was a ghostly galleon tossed upon cloudy seas." (The moon is a galleon.)

- Simile: A comparison between two unlike things using "like" or "as."

- Example: "Her smile was as bright as the sun."

- Personification: Attributing human characteristics, emotions, or behaviors to inanimate objects or abstract ideas.

- Example: "The wind whispered secrets through the trees."

- Allusion: An unexplained reference to a person, place, event, or literary work outside of the text itself. It enriches the text by invoking a shared cultural or literary context.

- Example: "He was a true Romeo with the ladies." (Alludes to Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet).

- Hyperbole: Exaggeration for emphasis or effect.

- Example: "I'm so hungry I could eat a horse."

- Oxymoron: Combining two contradictory terms or ideas for effect, often revealing a deeper truth.

- Example: "Jumbo shrimp," "living dead."

- Paradox: A statement that appears self-contradictory but contains a deeper truth upon closer examination.

- Example: "Less is more."

- Imagery: Descriptive language that appeals to any of the five senses (sight, sound, smell, taste, touch), creating a vivid mental picture or sensory experience for the reader.

- Example: "The crisp, cool air bit at her bare skin as she breathed in the sweet scent of pine needles."

- Conceit: An elaborate, often surprising or far-fetched, comparison between two very different things, typically extended throughout a poem.

- Example: John Donne's "The Flea" compares a flea biting lovers to their shared blood, a union that should precede marriage.

- Apostrophe: Addressing an absent person, an abstract idea, or an inanimate object directly.

- Example: "Oh, Death, be not proud."

- Diction: The poet's deliberate choice of words. This includes the vocabulary, phrasing, and stylistic choices, all of which contribute to the poem's tone, mood, and meaning.

- Example: Using archaic words creates a formal or ancient tone; colloquialisms create an informal, modern tone.

- Connotation & Denotation:

- Denotation: The literal, dictionary definition of a word.

- Connotation: The emotional associations or cultural implications suggested by a word, beyond its literal meaning.

- Example: "Home" (denotation: a place of residence; connotation: warmth, family, comfort, security).

- Motif: A recurring element, idea, image, or symbol that appears throughout a work, helping to develop a theme.

- Example: The recurring image of birds or flight often symbolizes freedom in literature.

- Irony: A contrast between expectation and reality.

- Dramatic Irony: The audience knows something a character doesn't. (While often theatrical, it can apply to narrative poems).

- Verbal Irony: Saying the opposite of what you mean (sarcasm).

- Situational Irony: When the outcome is the opposite of what's expected.

Sound & Rhythm: The Music of Language

Poetry is meant to be heard, even if silently. These devices shape the auditory experience of the poem.

- Alliteration: Repetition of the initial consonant sound in a series of words.

- Example: "Peter Piper picked a peck of pickled peppers."

- Assonance: Repetition of vowel sounds within a series of words that don't necessarily rhyme.

- Example: "The light of the fire is quite a sight."

- Consonance: Repetition of consonant sounds within a series of words, often at the end of stressed syllables, but not necessarily rhyming.

- Example: "Mike likes his new bike."

- Onomatopoeia: Words that imitate the sound they represent.

- Example: "Buzz," "hiss," "bang," "sizzle."

- Euphony: Words and phrases that combine to create a pleasant, smooth, and melodious sound, often with soft or liquid consonants (L, M, N, R, W, Y).

- Example: "Season of mists and mellow fruitfulness."

- Cacophony: Words that combine to create harsh, jarring, and discordant sounds, often using plosive or guttural consonants (T, P, K, D, B, G).

- Example: "With bloody blows and ghastly gashes grim."

- Rhyme: The repetition of similar sounds, usually at the end of lines in poetry.

- End Rhyme: Occurs at the end of lines.

- Internal Rhyme: Occurs within a single line or between words in the middle of different lines.

- Slant Rhyme (or Near Rhyme): Words that have similar but not identical sounds, often sharing the same consonant sound but a different vowel sound.

- Example: "Soul" and "all."

- Refrain: A line or group of lines that regularly repeats throughout a poem, often at the end of stanzas.

- Example: "Quoth the Raven, 'Nevermore.'"

Structure & Form: The Architecture of Verse

These elements define the poem's physical layout and rhythmic backbone.

- Line Break: The termination of one line of poetry and the beginning of a new line. It's a fundamental structural choice that impacts rhythm and emphasis.

- Enjambment: The continuation of a sentence, phrase, or clause across a line break without a pause. It creates a sense of flow and can build tension.

- Example: "I think that I shall never see / A poem as lovely as a tree."

- End-Stopped Line: A line of poetry where a sentence or clause concludes at the end of the line, usually marked by punctuation (period, comma, semicolon).

- Example: "I hear America singing, the varied carols I hear; / Those of mechanics, each one singing his as it should be blithe and strong;"

- Caesura: A pause or break within a line of poetry, usually indicated by punctuation (a comma, semicolon, or dash). It creates a dramatic pause or alters the rhythm.

- Example: "To be, or not to be: that is the question."

- Stanza: A group of lines forming the basic recurring metrical unit in a poem; a verse.

- Couplet: A two-line stanza.

- Quatrain: A four-line stanza.

- Sestet: A six-line stanza.

- Cinquain: Historically, any five-line stanza; more recently, refers to specific five-line patterns.

- Rhyme Scheme: The pattern of end rhymes in a poem, typically represented by letters (e.g., ABAB, AABB).

- Example: In an AABB rhyme scheme, the first two lines rhyme, and the next two lines rhyme.

- Meter: The rhythmic pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables in a line of poetry. It's measured in "feet."

- Foot: A basic unit of meter, usually consisting of two or three syllables.

- Iamb: Two syllables: unstressed, stressed (da-DUM, e.g., "define").

- Anapest: Three syllables: unstressed, unstressed, stressed (da-da-DUM, e.g., "understand").

- Dactyl: Three syllables: stressed, unstressed, unstressed (DUM-da-da, e.g., "poetry").

- Common meters by line length:

- Pentameter: A line with five metrical feet.

- Tetrameter: A line with four metrical feet.

- Blank Verse: Poetry written in unrhymed iambic pentameter. It has a formal structure but avoids the musicality of rhyme.

- Free Verse: Poetry that does not adhere to a regular meter or rhyme scheme. It allows for greater flexibility in rhythm and form, often mimicking natural speech patterns.

- Ballad: A type of poem that tells a story, often with a simple, narrative structure, four-line stanzas, and an ABCB rhyme scheme.

- Ballade: A medieval French form of lyric poetry with a strict "ababbcbc" rhyme scheme, typically three eight-line stanzas, and a shorter four-line envoi.

- Envoi: A brief concluding stanza, often summarizing or dedicating the poem, typically found in forms like the Ballade.

From Page to Insight: How to Analyze a Poem's Devices and Structure

Now that you have your toolkit, how do you put it into practice? Analyzing a poem isn't about finding every single device; it's about understanding how the poet's choices contribute to the overall effect and meaning.

Step-by-Step Poetic Exploration:

- First Read: Absorb and React. Read the poem aloud, or at least mentally. Don't worry about analysis yet. Just experience it. What is your initial emotional response? What images stand out? What's the general subject?

- Second Read: Identify the Core. Who is speaking (the speaker/persona)? To whom are they speaking (the audience)? What is the central subject or problem? What's the setting (time and place)?

- Map the Structure:

- Stanzas: How many? Are they regular in length?

- Line Length: Are lines generally short or long? Does this affect the pace?

- Rhyme Scheme: Try to mark the end rhymes (ABAB, AABB, etc.). Is there a consistent pattern? Is it blank verse (unrhymed iambic pentameter) or free verse (no consistent rhyme or meter)?

- Meter: Can you detect a dominant rhythm? Clap it out. Do certain syllables feel stressed? (Don't get bogged down here; an overall sense is often enough.)

- Line Breaks: Look for enjambment (lines flowing without pause) versus end-stopped lines (lines ending with punctuation). How does this affect the flow and emphasis?

- Spot the Devices:

- Imagery: What senses does the poem engage? Underline vivid descriptions.

- Figures of Speech: Look for metaphors, similes, personification, hyperbole, or allusions. What two things are being compared? What external knowledge is being invoked?

- Sound Devices: Notice alliteration, assonance, consonance, or onomatopoeia. Do certain sounds repeat? Are they harsh (cacophony) or pleasing (euphony)?

- Repetition: Are any words, phrases, or lines repeated (refrain, anaphora)? What effect does this create?

- Diction & Tone: Are the words simple or complex? Formal or informal? Does the language suggest a specific mood (e.g., melancholy, joyous, angry)?

- Connect Devices to Meaning: This is the most crucial step. For each device or structural choice you identified, ask:

- Why did the poet use this?

- How does it contribute to the poem's meaning, mood, or theme?

- What effect does it have on you as the reader?

- Does the rhythm create a sense of urgency, calmness, or sadness? Does a metaphor reveal a new insight about the subject? Does an allusion deepen the emotional resonance?

For example, consider how Eugene Field crafts his lullaby, Wynken Blynken and Nod. The simple AABB rhyme scheme, the consistent rhythm, and the personification of stars and a wooden shoe into sailing adventures all contribute to a gentle, whimsical, dreamlike atmosphere perfect for a bedtime story. The structure and devices work in harmony to transport the reader (and listener) into a peaceful, imaginative world.

- Formulate Your Interpretation: Based on your observations, what do you believe the poem is trying to communicate? How do the various elements work together to achieve this? Support your interpretation with specific textual evidence (quotes!).

Beyond the Basics: Common Questions & Deeper Dives

Understanding literary devices and poetic structure might seem daunting, but it opens up a world of insight. Here are answers to some common questions:

Do all poems have a strict structure and obvious devices?

No. While many poems, especially older ones, adhere to strict meter and rhyme schemes (like sonnets or ballads), free verse poetry specifically liberates itself from these constraints. Even free verse, however, still employs literary devices like imagery, metaphor, and sound play (e.g., assonance) to achieve its effects. The "structure" in free verse might come from line breaks, stanza breaks, or thematic repetition rather than rigid meter.

Are literary devices just for English class, or do they have real-world relevance?

Literary devices are fundamental to all forms of communication, not just poetry. They are the backbone of persuasive speeches (rhetorical devices like anaphora, hyperbole), engaging prose (metaphors, imagery), song lyrics, advertising slogans, and even everyday conversation. Learning to identify them enhances your critical thinking, communication skills, and appreciation for how language shapes thought and emotion in every context.

Is there a "right" way to interpret a poem?

While some interpretations are more strongly supported by textual evidence than others, there isn't usually one single "right" interpretation. Poetry often invites multiple readings and personal connections. The goal of analysis is not to find the only meaning but to develop a well-supported interpretation based on the literary devices, structure, and language choices the poet made. Different readers may emphasize different elements, leading to varied but equally valid insights.

Your Toolkit for Poetic Exploration

By familiarizing yourself with these essential literary devices and elements of poetic structure, you're not just learning definitions; you're acquiring a powerful set of tools. These tools allow you to disassemble a poem, examine its intricate components, and reassemble it with a profound understanding of its artistry. The more you practice, the more intuitive it becomes. Pick a poem you love, or one you've always found challenging, and try applying these steps. You'll be amazed at the layers of meaning, emotion, and craft you uncover, transforming your reading experience from passive reception to active, insightful engagement. Happy exploring!